Popcorn: The Timeless Snack That Popped Into History 9,000 Years Ago

Popcorn, crispetas, rosetas, poporopos… whatever name each region has given them, it is a global snack that has become almost a symbol of the movie industry. And although this industry popularized it almost 100 years ago, this snack has accompanied me throughout my childhood, at children’s parties, at posadas, at festivals, after school, in the parks… and of course, also at the movies.

But did you know that the history of popcorn began not 100 years ago, not 500 years ago, but approximately 9,000 years ago, with a wild grass called teocintle?

From grass to corn, a biological triumph.

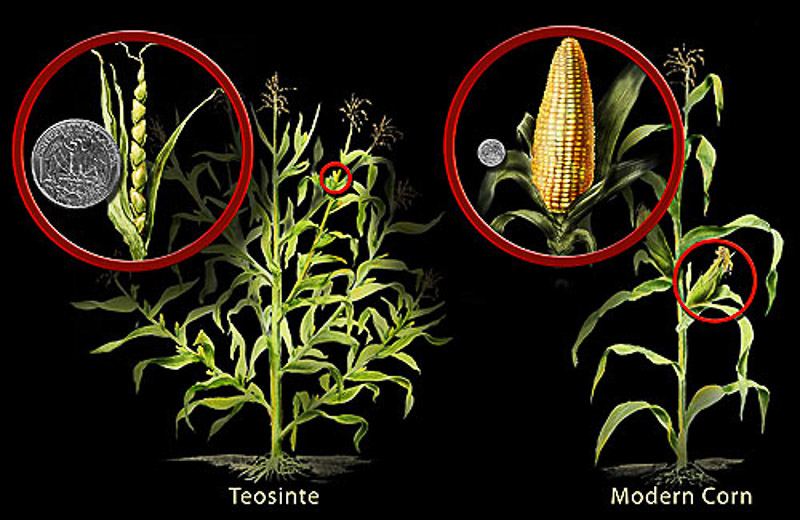

In 1977, Nobel Prize-winning geneticist George Wells Beadle published a seminal study on the origin of corn, where he proposed something that changed the way we understand this crop: that corn did not arise from a mixture of many plants, but was domesticated from a single wild species, known as teocintle or teosinte, specifically the subspecies Zea mays parviglumis, which grows in the Balsas River region of Mexico.

If you look at a teocintle plant, it is hard to believe. It looks nothing like the corn we know today. It is a slender, multi-branched shrub with small, hard kernels enclosed in a tough husk. However, Beadle showed that teocintle and maize are so similar in their genetic structure that it is possible to cross them and obtain hybrid plants, confirming that maize may have evolved from teocintle.

Although it has not yet been determined with absolute precision where and when the domestication of maize began, most scientific studies suggest that it was in southwestern Mexico, approximately 9,000 years ago, from the teocintle. Beadle arrived at this estimate based on genetic studies, where he cultivated hybrids between maize and teocintle in extensive experimental plots and demonstrated that only five key genes were sufficient to transform a branched plant with bitter grains into a large ear with a single ear and soft grains.

The most recent archaeological studies have found maize pollen in Oaxaca, dating back between 7,400 and 6,700 years BC, and fossil seeds from central Mexico dating back 5,000 years(Vargas, 2014). This transformation process was the result of patience, observation and careful selection by early Mesoamerican farmers. For many scientists, this domestication of maize is considered one of the most remarkable agricultural feats in history, comparable in importance to other great domestications of the ancient world.

And the most fascinating thing… is that the teocintle pops. So, perhaps, the first popcorn was born long before modern corn.

I have not been able to read Beadle’s full article directly, but this process and everything he discovered is explained very clearly in a video I found. It is called “Popped Secret: The Mysterious Origin of Corn”, and it was made by BioInteractive, which is part of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. If you are curious to see how scientists discovered that corn comes from the teocintle, you can watch it there.

Popcorn and its way through America

Not all corn varieties pop. Although the popcorn we eat at the movies comes from only one or two modern varieties of popcorn (butterfly and mushroom), in Mexico there are many native varieties, such as Palomero Toluqueño, Chapalote and Nal-Tel, among others. In Peru, there is a variety that does not explode like popcorn, but is roasted and slightly inflated: this is the chulpe corn, which is used to prepare a traditional snack called cancha.

Evidence of popcorn consumption in Peru has been found dating back more than 6,700 years to 6,700 years. The routes of exchange and trade of products between different peoples are not something modern. There were already connections that took corn from Mesoamerica south to Chile, north to the St. Lawrence River (Saint-Laurent) and also to the Caribbean, where corn was already being cultivated long before European contact, as part of networks that united the peoples of the continent. All this made it possible to share a history that, perhaps, was not written in words, but in what was eaten.

Popcorn, an offering to the gods

Popcorn was much more than a snack for ancient Mesoamerican peoples, it was part of rituals and sacred offerings. In the Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún mentions that during the festivities dedicated to Opochtli, god of water and fishing, the Nahua people offered various symbolic elements: pulque, green corn canes, flowers, copal, and also popcorn.

This popcorn, called momóchitl, was prepared in special pots that “sounded like bells”. In the ceremony this toasted corn was sown, or rather scattered in front of the god. Sahagún describes it as follows:

“…they also sowed in front of it a roasted corn that they call momóchitl which is a kind of corn that when roasted bursts and uncovers the kernel and becomes like a very white flower: they said that these were hailstones, which are attributed to the gods of water.”

For them, these small white flowers were not only food, they were hailstones, celestial gifts, a connection to the Tlaloques, gods of water. Each burst of grain symbolized fertility, rain, and the life cycle.

Necklaces and memory

Bernardino de Sahagún also described how the Mexica made necklaces of flowers, grains, and popcorn for use in important rituals and ceremonies. These necklaces, more than ornaments, were sacred symbols, offered to the gods, worn by priests, warriors, and maidens in solemn dances.

What is perhaps surprising is that these customs did not disappear. In Mexico, even today, similar necklaces are still made to embellish the offerings and accompany the celebrations. Necklaces of flowers, fruits, seeds, and still in some villages of the Matlatzinca region, in central Mexico, of popcorn. Many may not know where the tradition comes from, but it is there, alive, as a memory woven into the festivities of patron saints, weddings or the Day of the Dead.

Hands continue to braid necklaces, decorate saints, tombs and altars; perhaps with the same motive as those ancestors, to honor life; perhaps for other reasons. But if we look carefully, we discover that many of these things that seem small or common to us, have been with us for centuries or even millennia.

How did ancient Mesoamericans eat popcorn?

They did not use oil or butter. Perhaps, at some point, a grain of teocintle fell into the embers and burst by accident. Some accounts say that they also made them with hot ashes, and later in clay pots and accompanied with chili.

At home, my parents made popcorn without machines, without microwaves, just a pot, a little oil and the kernels. They moved the pot with patience, so they wouldn’t burn, waiting for that moment when the first pop would break the silence. This is how we continue to make them, simple, as before.

Making popcorn is not just a whim, it is honoring those who watched the teocintle and did not despise it, but watched it grow, helped it to be. It is to believe again that food is more than filling the stomach; it is to feed the soul; it is to respect the work of those who cultivate the land. My ancestors did not use our words, but they knew about corn and soil, water and chili.

How to make easy popcorn in 10 minutes - no machine, only pot

18

mugs10

minutesIngredients

150 g 3/4 cup of popcorn

2-3 tablespoons 2-3 cucharadas soperas of vegetable oil (corn or sunflower)

1/2 teaspoon 1/2 cucharadita salt. Adjust to taste.

Directions

- Place a large pot (ideally with a thick bottom) over medium-high heat. Heat for 2 to 3 minutes without oil.

- Add the 2 to 3 tablespoons of oil. Once hot, add a single kernel of corn. If it starts to swirl and sizzle, the oil is ready.

- Pour in the ¾ cup of popcorn. Immediately cover the pot.

- Hold the pot by the handles (use gloves or towel if necessary) and gently rock the pot back and forth every 5-10 seconds. This prevents the grains on the bottom from burning and ensures even cooking.

- At first it will be slow, then it will accelerate. When the interval between one burst and another is longer than 3-4 seconds, turn off the fire.

- Leave the pot covered for 30 seconds more to finish popping the remaining grains.

- Carefully uncover the pot, and while the popcorn is still hot, sprinkle salt to taste and any other seasoning you prefer: chili powder, melted butter, lemon, or whatever strikes your fancy. Replace the lid on the pot and stir gently, or mix with a large spoon, so that the flavor is evenly distributed throughout each kernel.

Notes

- Yields between 18 and 24 cups of ready-made popcorn, enough to fill a large pot and share with several people.

Did you make this recipe?

Tag @mealnstock on Instagram and hashtag it with

Like this recipe?

Follow @Meal&Stock on Pinterest

Join our Facebook Page!

Follow us on Facebook